Happy New Year, everyone! As I write this, 2017 has just begun and I’ve got “experimental” Soup Joumou cooking. It might not be the certified goodness that my Mom blessed the family with a few days ago, but it is filling the house with the right smells for continuing a thread I started in With Print Comes Power and Long Life.

A story has long circulated that Haitian families like mine eat Soup Joumou because our ancestors were supposedly forbidden to eat it during slavery. Once the Avengers of the New World had wrapped up Batay Vètyè and sent Napoleon’s boys back into the sea, it was time to eat! It’s for this reason that people like “Culinary Curator” Nadege Fleurimond call it “freedom soup.”

Even if the story is more myth than history, the ritual is meaningful and the soup is delicious. The latter is not just my opinion, but a fact supported by many sources such as the footage found in the documentary embedded below.

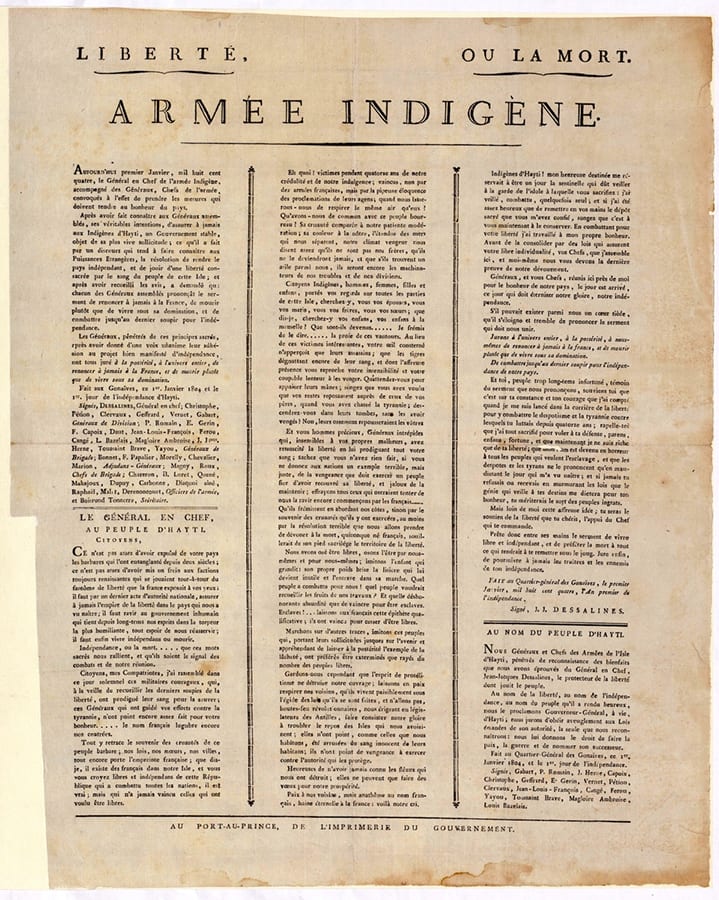

Whatever place our soup originally held, we know for certain that print was part of that first New Year’s Revolution. On January 1st in 1804, Haitian leaders under the command of General Jean-Jacques Dessalines assembled in the city of Gonaïves to formally proclaim independence, recognize Dessalines as governor general, and renounce France. Dessalines delivered a speech in Kreyòl (the dominant language among Haitians) and there was a public reading of a proclamation, written in French, that we now call “The Haitian Declaration of Independence.”

With print, the authoritative utterances of Haiti’s founders were given material expression and publicized to the wider world.

As noted in The Haitian Declaration of Independence: Creation, Context, and Legacy:

The Declaration rested on multiple authorities. The first was the authority of Dessalines himself, as “Général en Chef” at the head of his army. The second, derived from the first, was Dessalines’s voice speaking to his people and in their name. In similar contexts—most notably, again, the infant United States in the summer of 1776—the next layer of authority would have been that of manuscript publication, often with affirmatory signatures attached. Although we can infer the existence of such a stage of authority, and authorization, the textual trace of it no longer exists. Finally, the last, but most immediately material and most enduring, was the authority of print which publicly settled and circulated the form and content of otherwise dynamic and shifting texts. There seems to have been no printing press in Gonaïves, and the pamphlet version of the Declaration appeared from the “Imprimerie du Gouvernement” at Port-au-Prince, where it became one of a sequence of public utterances issued in late 1803 and early 1804. Enlightenment ideals of publicity demanded that such statements be made not just before witnesses but addressed to the wider world of international opinion.[i]

With print came power.

As the Ancestors used this document in 1804 to proclaim independence and announce the birth of the only nation founded by formerly enslaved people who beat their oppressors, my wife and I used it in 2012 to announce how we would carry that heritage into the future. My wife was pregnant and we would soon be joined by our daughter.

Let me tell you why this was peak stagecraft.

As a physical thing, the document we now refer to as the Haitian Declaration of Independence vanished during the latter part of the nineteenth century. The forceful words of General Dessalines, as written by his secretary Louis Félix Boisrond-Tonnerre, had been passed down through subsequent print and culture, but official originals of the document were lost due to factors including inadequate archiving, natural disasters, and the vicissitudes of politics. While we can view a permanent display of the USA’s Declaration of Independence at the Rotunda for the Charters of Freedom, my relatives and most immediate ancestors had never enjoyed the opportunity to be in the physical presence of Haiti’s birth certificate.

The Haitian Declaration of Independence Document MFQ 1/184 National Archives, U.K.

Well, that was about to change. While working on her dissertation at Duke University on the early period of Haiti’s independence, a historian named Julia Gaffield adopted an approach to archival research that recognized the interconnectedness of the Atlantic World including Haiti. Instead of conducting her research exclusively in Haiti, she performed archival research in Haiti, Jamaica, Great Britain, France, the United States, The Netherlands, and Denmark. Gaffield found relevant documents in archives throughout what would have been early Haiti’s “wider world of international opinion,” but in The National Archives of the United Kingdom she ultimately found two surviving government-issued originals of the Declaration. This was huge news back in 2010 and was deeply resonant coming so soon after the deadly earthquake of earlier that year. When you get a chance, consider reading a piece Gaffield wrote in The Appendix for more of the story and visit her site at https://haitidoi.com/.

Fast forward to early 2012 to when I brought a few relatives to see an exhibit at The New-York Historical Society. Revolution! The Atlantic World Reborn was “the first exhibition to relate the American, French, and Haitian Revolutions as a single, global narrative.” That approach alone would have been enough to capture my attention, but as part of the exhibit, one of the recently found originals of the Declaration was being displayed to the public for the first time. Though I had already seen the exhibition, and stood before the Declaration, the experience was heightened by deeper second looks and witnessing my relatives experiencing it for the first time. And then, after my family had touched the Ancestors through the exhibition’s story and the print they had left behind, I announced the coming of our baby girl. Through us the Ancestors continue. And with print came life.

[i] Armitage, David, and Julia Gaffield. 2016. “The Haitian Declaration of Independence in an Atlantic Context”. In The Haitian Declaration of Independence: Creation, Context, and Legacy, ed. Julia Gaffield. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press , p. 1-22.

Andy Solages connects people and organizations with technologies to improve professional experiences and business results. Andy is a monthly contributor to Print Media Centr’s News from The Printerverse and a regular participant in #PrintChat on Twitter.

Treat yourself to more Andy: Twitter | LinkedIn | andysolages.com