My interest in history and my use of popular artificial intelligences have me thinking about how we extend our human selves in terms of power and existence through our technology. Clive Thompson’s Smarter Than You Think (which I wrote about here) informs these thoughts, and I hear whispers of Carl Sagan’s famous words on the magic of books.

Alexa, Siri, Google, and Cortana haunt our house across different rooms and devices. Per my daughter, they are all sisters who go on adventures together, but don’t have bodies. Anyway, I speak a word of power and a helper spirit performs a task, saving me a sliver of time and effort. While I cook, I say the equivalent of “let there be NPR” and it is done. “Oh, Laurent Dubois will be speaking at the Schomburg Center and discussing his book on the banjo? He’s one of my favorite historians. Add that event to my calendar.” No opening of apps. No writing. Just spoken spells and a comprehensive record of my personal life in the hands of strangers.

Through this technology, I am enhanced and I am recorded. I work what would have once appeared to be miracles and my life is etched in the cloud. Impermanence is still a thing, but part of what is me is not limited to my physical body.

Maybe it’s a function of the people in my circles, but I haven’t noticed anyone freaking out about Amazon Echo or Google Home. But someone somewhere should be freaking out because that has been our pattern as human beings when new technology, which may impact cognition, are introduced or become popular. As Thompson discusses in his book, print and writing were no exception.

Socrates feared writing would destroy the capacity to memorize information and ruin Greek traditions of debate and dialectic. The old gadfly liked his thought palaces.

Ye Mengde of 10th century China worried that the wider availability of written records made possible by China’s advanced printing technology would weaken memories and cause errors to be repeated without end.

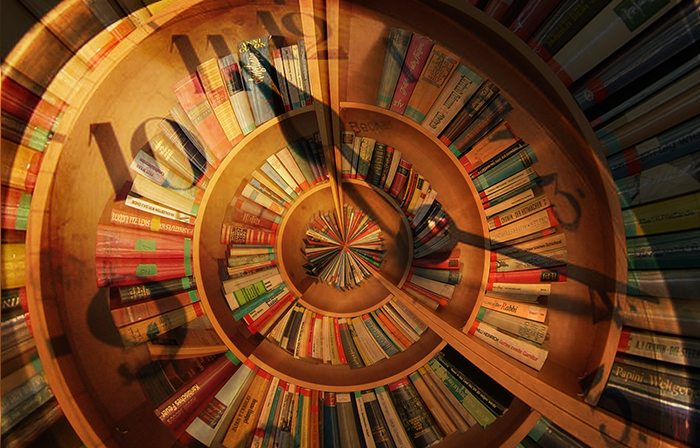

Print gave us scary new powers, sure. But the technology (e.g. Plato’s writing) also means that time and hemlock don’t preclude us from connecting with Socrates.

As I feed my geek with my annual pre-January 1st review of Haitian history I’ve been thinking about the powers of print and the role print played and did not play during the Haitian Revolution. In an article published in Aeon, Laurent Dubois (the aforementioned historian) said “But as when we study the Haitian Revolution, we need to constantly remind ourselves that these texts are mostly traces of a much larger set of conversations that did not take place through writing, but rather through speaking, organising and debating in the midst of military and political action.”

The people of what was then Saint-Domingue spoke Haitian Kreyòl at a time before the language was written and had an independent orthography. With the available writing produced by people literate in French, we know the texts leave significant gaps in our knowledge. So, while Google and Amazon (or their successors) will be able to give future historians precise information about how often Andy Solages listened to Buzzfeed’s “Another Round” podcast, it’s not as easy to find records of Henri Christophe talking smack about Sans-Souci (the freedom fighter not the palace).

But print still had a role. And still gave power and recorded pieces of the lives of those who authored it. For example, at her Dessalines Reader website, the historian Julia Gaffield has posted texts attributed to revolutionary leader Jean-Jacques Dessalines. Through these texts, this technology, Dessalines amplified his power to communicate, and in our time, we have a better record of what he thought and did.

Non-authors and illiterate people also drew power from print. There are stories of pamphlets and dubious “royal decrees” used to propagandize and support rumors of emancipation or modest improvements like “free days” for enslaved people. If what was written supported the preferred narrative, cool. But even if not, when speaking to illiterate people, it was possible to wield the credibility and authority facilitated by documents and claim they say whatever is in the speaker’s interest.

I’ve been spending more time looking at original texts, even when I can’t fully understand them. I just picked up Tropics of Haiti: Race and the Literary History of the Haitian Revolution in the Atlantic World, 1789-1865 by Dr. Marlene Daut. It has been described as “the first exhaustive study of the transatlantic print culture of the Haitian Revolution” and I can’t wait to dig into it (also my friend Kreyolicious just interviewed the author).

The texts are talismans: magic as information technology through which our ancestors communicated and magic as physical things through which we touch the reality of our predecessors. Electronic representations and reproductions in books are wonderful, but I love seeing them in museums. Watch this space for a story I plan to share with the Printerverse, involving a long lost but highly significant historical text and how the person and people associated with it still touch us today.

Andy Solages connects people and organizations with technologies to improve professional experiences and business results. Andy is a monthly contributor to Print Media Centr’s News from The Printerverse and a regular participant in #PrintChat on Twitter.

Treat yourself to more Andy: Twitter | LinkedIn | andysolages.com

One Response